Samoyeds: The Versatile Beauty

Text and photos by Kent & Donna Dannen

The smiles, the pointing fingers, the wondrous raving by complete strangers over the dog’s beauty–a Samoyed owner soon learns what it is like to possess one of the most beautiful breeds of the canine world.

The long, sparkling white coat contrasting with dark nose and eye rims causes the Samoyed to look glamorous. The upright, pointed ears, long muzzle, and plume like tail curled over a moderate-sized body identify it as one of the romantic husky breeds. The dark lip lines accent the expressive Sammy “smile,” which transforms the dog’s admirers into its friends.

“What kind of dog is it?” the wide-eyed admirers ask.

“A Samoyed,” the owner replies, perhaps putting the accent on the first syllable or more commonly on the second, but always trying to emphasize the “d” on the end of the name.

“Oh, a Sam. . .oyon. Will it bite?”

“No,” the owner laughs, ignoring the mispronunciation. “This dog loves you as much as me.”

Happily plunging fingers deep into the sensuously thick coat, the questioner enjoys the dog’s obvious pleasure in being petted as it cuddles up to the petter. In this way, the Samoyed’s great beauty and friendly personality snares another admirer.

Yet, as a tee-shirt popular among Samoyed owners proclaims, the working Samoyed is more than a pretty face. Rugged and sturdy under the masses of hair, modern Sams are multipurpose descendants of dogs first developed many centuries ago by nomadic Samoyed tribes of north-central Siberia, one of the toughest homelands on earth. Preserved in isolation by the ruggedness of this Arctic territory, the Samoyed remained mostly unchanged over several thousand years, making it today one of the oldest breeds.

The Samoyed tribes were semi-nomadic reindeer herders. In summer, they grazed their reindeer on the ground-hugging plants of the Arctic tundra. In winter, they retreated with their herds to subarctic forests. To supplement their livelihood, Samoyedic tribes hunted and fished. Throughout the year, these nomads lived in tents called “chooms.” Covered with reindeer hides or bark, chooms were conical and often banked with earth or snow in winter.

To Samoyedic wanderers, only reindeer were more significant than their precious, multipurpose dogs. Occasionally, a dog’s hide with its long hair might end up as part of human clothing. Usually, though, the dogs helped the Samoyedic tribes herd their reindeer and hunt wild animals even as daunting as polar bears. The dogs’ bodies added warmth to the chooms during Siberian winters and companionship in the wilderness. Samoyeds also transported their masters across the snow in dog sleds.

This wandering lifestyle may account for the Sam’s inclination to wander today, making a securely fenced yard or constant use of a leash necessities for keeping a Samoyed safe. A nomadic heritage may also account for the breeds adaptability to various living conditions. Sams can do well in apartments and urban, suburban, or rural houses so long as they receive plenty of exercise under control of fence or leash. Lack of a fenced yard does place considerable demand for leashed walks on the owner, who will benefit tremendously also from the time-consuming exercise. Samoyeds also seem to adapt to the heat of southern states, if they can find refuge in air conditioning with the cool times of day available for exercise.

The one thing a Samoyed cannot tolerate is being ignored or living without companionship. With its heritiage of living and working with nomadic people on a daily basis, the Sam must be an integral part of its family rather than being constantly exiled to even a large fenced yard or comfortable kennel. An ignored Samoyed can do significant damage to property and even to itself, not out of anger but out of boredom. Most adult Sams can tolerate lack of humans during normal working hours, but Samoyeds should be part their owners’ lives during the rest of the day. Puppies of all breeds, of course, require special attention and lots of time during their formative weeks in a new home.

Regrettably, the Communist Revolution in Russia cut off western experience with the Samoyed people and their beautiful, multipurpose dogs. No significant breeding stock from Siberia influenced western Samoyed pedigrees after World War I.

Our best sources of information about the Samoyed people, their culture, and their dogs are the journals of a few turn-of-the-century polar explorers. These men went to Samoyed tribes to buy dogs to aid in the charting of unknown Antarctic and Arctic regions. Adventurers used Samoyed dogs to pull sleds and praised these dogs fervently, especially for their hard-working spunk and appealing temperaments.

A low percentage of the dogs of all breeds used on these explorations survived the expeditions. Because they were so appealing individually, and thus received special consideration, Samoyeds may have had a little better chance. Some Sams became pets of expedition members. Other Samoyeds went on display in zoos after serving on famous expeditions. Most importantly to the breed, English dog enthusiasts bought some of these dogs and established a breed standard.

The Samoyed looks much the same today as the dogs who pulled explorers’ sleds. Norwegian adventurer Fridtjof Nansen in 1893-94 tried to reach the North Pole with a Samoyed sled team. His records of his dogs’ weights and heights match the dimensions of today’s normal Samoyeds. Proper weight for a 21- to-23 1/2-inch male is around 60 pounds; a 19- to-21-inch female weighs 45 to 50 pounds. This size is a compromise between a somewhat smaller sprint-racing dog and a giant freighting dog. Many of the dogs originally bought in Siberia for polar exploration could have won championships in modern dog shows.

Expedition dogs from the western Samoyedic tribes often were spotted, black, or brown, unexceptable in today’s show ring. However, Alexander Trontheim, a Russian who bought dogs for foreign explorers, tended to shop among Samoyed tribes in eastern Siberia. These remote people always bred dogs colored like modern purebred Samoyeds, white, cream, or biscuit.

Some historians of the breed maintain that all Samoyeds are descended from just 12 individual dogs. This ancestral dozen all came under the care of English breeders, who established a registry and began competing with Sams in dog shows. Several were veterans of the 1894 Jackson-Harmsworth exploration of Franz Josef Land north of the Arctic Circle. One dog was salvaged from an Australian zoo where it had been warehoused after completing the Borchgrevink Antarctic expedition. Another Samoyed survived the North Pole expedition led by Italian adventurer the Duc d’ Abruzzi. Alexander Trontheim supplied some others and some English breeders themselves followed the route of this Russian dog broker to the Siberian source before World War I. (We should have mentioned this effort to a potential puppy buyer in Colorado who balked at the distance when we referred her to a litter bred in central Wyoming.)

Befitting its romantic, glamorous appearance, the Samoyed that first emigrated to America came in 1904 as companion to Princess de Montyglyon, of the Holy Roman Empire’s ruling family. That dog had been a gift from the Grand Duke of Russia, the Czar’s brother.

The breed’s aristocratic looks were inconsistent with its egalitarian attitude and working spirit, and Samoyed breeders in America emphasized canine virtues that harmonized with the American work ethic. Breeding and exhibiting dogs they imported primarily from English show stock, American breeders preserved sledding abilities that had served well the English polar explorers and nomadic Siberian tribes.

A sound body free of genetic faults was critical to this effort. Though the Samoyed breed sometimes produces genetic flaws found in many canines, careful screening of breeding stock by reputable breeders has kept these problems to a minimum. Puppy shots given by a veterinarian generally come along with a general exam that provides warning of any heart defects. Sire and dam should have had their hips X-rayed and examined by canine orthopedists to be sure of freedom from hip dysplasia. Better yet is for all eight grandparents as well to have been X-rayed and cleared.

Sire and dam should have been examined by a canine ophthalmologist also to be sure they are free of progressive retinal atrophy, glaucoma, cataracts and retinal dysplasia. Nordic breeds, which include the Samoyed, are said to have a higher than average rate of cataracts and glaucoma, though the incidence of these problems seems to have remained low enough to avoid a major concern among Sammy enthusiasts.

Puppies sold as potential show and breeding prospects also should have their eyes examined, although this may present a logistical problem. An ophthalmologist can clear eyes as free of problems as early as eight weeks. An eye problem cannot be diagnosed, however, until as late as 12 weeks because normal eye development sometimes masquarades as disease. Since the ideal time to send puppies to a new home is in the ninth week, it may be up to the new owners rather than the breeder to get eye checks done.

In the 1950s, Rex of White Way was a Samoyed from California who was well-known for his working attitude and accomplishments. Agnes Mason, who bred Rex, had lived in Alaska and maintained sled dogs with her father. She continued her interest in sledding when she moved to California and began breeding Samoyeds.

Mason showed off Samoyeds’ abilities through exhibitions with her dogs at parades, fairs, and dog shows. She hired Lloyd Van Sickle to drive her dogs on mail sled runs between Ashton, Idaho, and West Yellowstone, Montana. Rex of White Way was the mail run team leader. Rex also learned to parachute from small airplanes to help rescue travelers trapped in winter snow.

Though successful in dog shows, Rex evidently was too busy with other work to complete his championship. One story of this renowned dog has him pulled from a dog show to assist in the rescue of plane crash survivors in the Sierra Mountains. Rex also competed well in weight pulls. Rex of White Way is in the pedigrees of many of the top working Samoyeds today. His drive and determination to pull have stamped these characteristics on many of the breed’s modern bloodlines.

It might seem that this working heritage could be revealed physically in malformed Samoyed owners who have one arm stretched out longer than the other by their pet’s pulling on the end of a leash. While walking their dogs, Sam owners often hear comments from passersby such as, “Now just who is taking whom for a walk?” This inconvenient tendency can be trained out of Samoyeds, who can distinguish when they should heel on lead and pull in harness.

The Samoyed may have fared better under its primitive owners than did breeds developed by other Arctic people. Tribal Samoyed breeders must have loved their dogs greatly to create gentle animals that dote on children and have basically calm, predictable temperaments. As living blankets, Sams often brought comfort to Samoyed people in Siberia’s biting cold winter nights. In warm, modern homes, many Samoyeds prefer to sleep next to (or in) their masters’ beds, despite the hot discomfort of their heavy, double coats.

Such devotion does not cause a Samoyed to loyally defend his owner or owner’s property. Sams usually trust and love all people and almost certainly will wag a tail at the burglar rather than exercise the toothy end. Warning barks as strangers approach his master’s property only mean the Sam is excited with the prospect of someone new to love. Its loud voice makes the Samoyed a very useful watch dog despite the breed’s total incompetence as an attacking guard dog.

Its light-hearted approach to life may reflect the general attitude of the original Samoyed people. In any case, the Sam’s happy-go-lucky outlook has contributed to the American Kennel Club’s description of the breed: “The big, white, smiling dog carries in its face the spirit of Christmas the whole year through.”

Mischieviousness typical of Sams adds challenge to puppy raising or obedience training. Bored Samoyeds make a hobby of destruction, greatly distressing Samoyed owners who have little time to spend on training their pets. Even the Sam who gets much attention and training stays awake nights dreaming up ways to frustrate the owner’s goals. When training becomes a game, though, training a Samoyed is fun. Many Sams have done well in obedience trials. As with most breeds, successful training also requires that the owner maintain the role of pack leader.

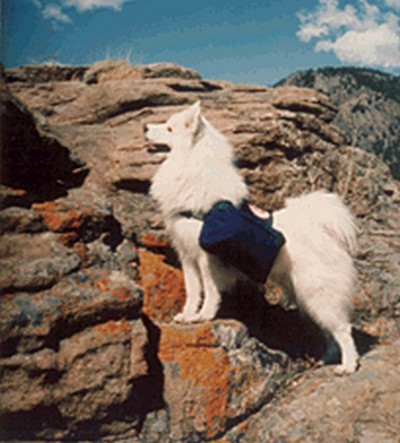

Samoyeds perform well in many outdoor activities and need a fair amount of exercise. Whether on a long excursion with dog packs fully loaded to 25 percent of the dog’s weight or on quick jaunts through the forest, working and playing with its master bonds the two through achieving a mutual goal.

The owner of only one Samoyed might enjoy skijoring, cross country skiing with a dog pulling on the end of a tow line. It looks something like water skiing and is not nearly as bold as it sounds.

A pair of Samoyeds can pull a dog sled, but three or four trained to work as team provide better power. Sledding exercises the owner as well as the dogs and fills winter with fun. The original Samoyeds used by the English to preserve the breed worked as sled dogs, having been bred in Siberia for that task. This alone should settle an everlasting dispute among today’s enthusiasts about whether Samoyeds were designed to pull sleds or herd reindeer. Because nomadic people cannot afford single-purpose possessions, Samoyed tribes likely used their dogs for both these purposes.

Sams are unlikely to be the fastest dogs in a sled race. However, a well-built, well-conditioned Sam team with a good lead dog sometimes may take advantage of a difficult trail that slows down specialized racing dogs more than the gritty and smart all-purpose Samoyeds. On a very hot or very cold day, on a steep or winding trail deep in fresh snow, Sams can make an advantage of adversity and beat normally faster breeds.

Of the three AKC breeds normally used for pulling sleds, Siberian huskies are racing sports cars. Alaskan malamutes are eighteen-wheel tractor-trailers. Jack-of-all-trades Samoyeds are station wagons. So infatuated are Sammy enthusiasts with the breed’s non specialized virtues, that they race more for the pleasure that team and driver take in the competition itself rather than for their slight chance of coming in first.

Some Samoyeds excel in weight pull events. Because they compete in weight categories against dogs of similar size, Samoyeds are among the top pullers as each dog tries to pull increasingly heavy loads until all put one dog fails to pull the heaviest weight. Some Samoyed owners use their weight pullers for hauling wood, rock, or whatever else needs moving from one point to another.

Most Samoyeds naturally do well in moving sheep from one point to another. As of this writing, five Samoyeds have earned recently devised AKC herding titles, and many Sams have passed herding aptitude tests. Training any dog for herding requires access to sheep, a difficult requirement for most American dog owners. No Samoyed owners have the opportunity to train their dogs to herd reindeer.

A few Sams have worked as gun dogs. The best ones have been obedience trained to retrieve dumbbells and have transferred that ability to retrieving game birds shot by a hunter. Not many Samoyeds have soft mouths, however. In their native Siberia, Samoyeds probably were used to run down big game. Arctic explorers found that Sams were talented at distracting polar bears until human hunters could shoot the bruins. Most Samoyeds, though, would rather kill prey for themselves and must be properly trained to be a real asset to the hunter. Some are proficient mousers, but woe to the floor lamp or light furniture that is between a Sam and its pestiferous prey.

The Samoyed Club of America (SCA) works for the improvement and recognition of the breed. When more and more people became interested in cultivating the various natural talents of the Samoyed, SCA established a series of working titles to identify and honor dogs with working abilities. These titles also encourage owners to exploit and enjoy these abilities. The dogs, which must be owned by SCA members, can earn points through eight types of work: sled racing, excursion sledding, skijoring, weight pulling, packing, herding, therapy, and special application (for work, such as movie making or assisting physically handicapped owners, which defies categorization.)

Earning 1000 points, verified by a sometimes daunting amount of paperwork for the SCA Working Committee, qualifies a dog to have the letters WS (Working Samoyed) appended to the end of its registered name. An additional 500 points creates a WSX (Working Samoyed Excellent). A recently created title highlights dogs who have earned 5000 points in at least four categories, Master Working Samoyed (WSXM).

The Organization for the Working Samoyed is another group that promotes the working ability of Sams. It awards annual trophies to top competitors in obedience, sled racing, and weight pulling and publishes a newsletter to inform members about training techniques, working dog care and nutrition, and other matters of interest.

All these types of work have a romantic character suited to the Samoyed and add to the flair of Sammy ownership. Americans have a special fascination with work and also with history. Therefore, American Samoyed breeders usually strive to produce dogs that “can do what the original Samoyeds did.” The original dogs, of course, were bred to help their owners survive in austere conditions under which no modern Samoyed owner lives on a daily basis.

The traits of modern Samoyeds that Americans define as working abilities are mostly creative anachronisms that vastly improve the quality (and perhaps the length) of life for dog and owner but are not absolutely necessary for survival. Therefore, debates occur among Samoyed breeders about whether it is better to breed for “type” (how the dog looks) or for working ability. It is very unusual for a Samoyed breeder to admit to breeding mainly for type (a derogatory accusation) though type is highly valued for winning in the show ring. This type-versus-performance debate goes on constantly within many breeds but fortunately remains largely academic among Samoyeds. The Samoyed breed displays no obvious split between working dogs and show dogs. The best Samoyed sled teams always are laced with AKC conformation champions, and all-champion teams are not remarkable.

We live near easily accessible alpine tundra, very similar to the treeless Arctic tundra with which Samoyeds were bred to cope. Therefore, we have come to realize that the Samoyed type, its beauty and charm, probably had essential survival benefits for its breeders on Siberia’s Arctic tundra.

Heart-stoppingly dramatic, the tundra is a perfect example of “It’s a wonderful place to visit, but I wouldn’t want to live there.” Because the wind that rules this domain is determined to kill any rebel or invader who dares to stand erect more than a few inches above the ground, humans feel alien and threatened as well as excited when visiting the tundra.

The tundra’s endless, jagged, hostile openness reduces humans who spend much time there to the mental stature of a tiny flower. The vastness in which humans count for absolutely nothing beats us down and humbles us. The high suicide rate among some groups of people who actually live on the Arctic tundra is easy to understand.

However, when we see Samoyed companions on the tundra, grinning at us with obvious joy in our presence and with no concern for anything but the present, our mood changes. Dogs so incredibly gorgeous lift our spirits by the overwhelming joy in their beauty. Their beauty and charm have the power to overcome the tundra’s anti-human intimidation. Perhaps machines could do the dogs’ draft work to help us survive on the tundra, but no internal combustion engine has the power to lift our spirits as do the dogs’ beauty and charm.

The tribal Samoyed breeders were clever. They made their dogs beautiful and charming as well as solid workers because beauty and charm had essential survival benefits for people living in an environment inherently hostile to human life.

Many modern people also live in ways and places that are unnatural and hostile to human survival. Evolved like dogs to live in small packs, we humans often live in huge urban herds that make individuals count for nothing. Formed naturally to finish our lives as part of a small pack, many humans now grow old living alone. Dogs very significantly help people survive happily in unnatural environments and situations just as Samoyed tribes survived on the tundra.

Therefore, among the Sam’s many working talents, the greatest may be its ability to be a wonderful pet that is totally devoted to its owners. Happiness for a Samoyed is being included in family activities, just as its ancestors were part of tribal families that migrated from one reindeer feeding ground to another. To share this happiness in constantly expanding amounts with the people fortunate enough to own a Samoyed is the breed’s finest work.